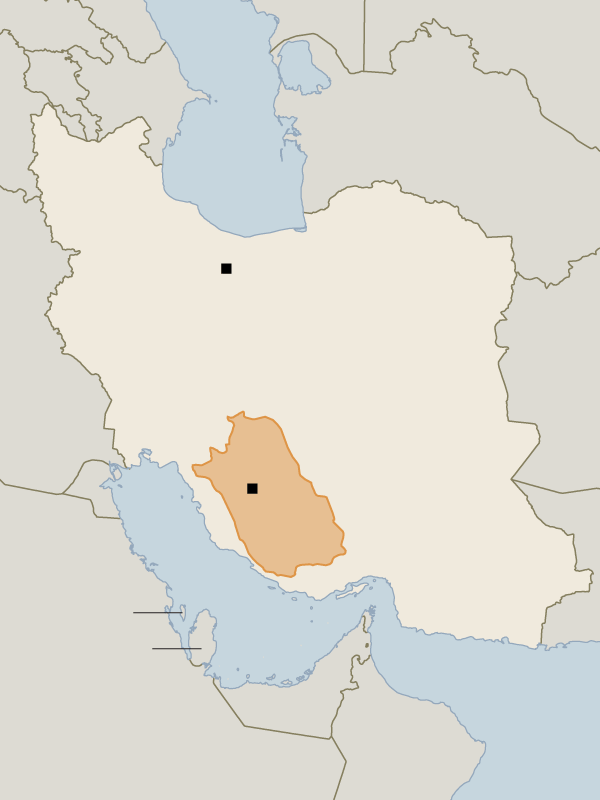

Sarough rugs, sometimes called Saruk or Sarouk rugs, are oriental rugs based on the exquisite, hand woven floor coverings that were first created in the 19th century by artisans living in Sarough, Farahan, Ghiassabad and other villages lying near the Iranian city of Arak in the central province of Markazi.

Where Do Sarough Rugs Come From?

The village of Sarough is located approximately 20 miles outside of Arak in the central Iranian province of Markazi, a city well-known for its carpet-making. These days, Sarough rugs do not necessarily come from Sarough, though. The term “Sarough” is reserved for all high-end Persian carpets from this region, carpets that are still woven by hand. The term “Arak carpet” is more commonly used for the machine-woven rugs that come from this area.

What Is the History of the Markazi Province?

Markazi is a region in Iran with a long history of human settlement. In the first century B.C., the province was the center of the great empire of the Medes, one of the four great powers of the ancient Near East.

The history of carpet-weaving in this region, however, only dates back to the 19th century when the demand for carpets for American markets spurred the creation of characteristic rugs that used the high quality wools and natural dyes found in the area. The delicate nature of the dyes were not quite bright enough for the American market, so often parts of the rugs were re-dyed a bright raspberry or blue color after they were imported into the United States. This is the origin of the Sarough rug’s distinctive color palette.

How Did Sarough Rugs Originate?

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the village of Sarough became renowned for exquisite, hand-woven carpets with floral designs that were primarily sold in the American market. Sarough rugs manufactured before the First World War showed a strong Turkish influence and tended to sport a classic central medallion design while rugs manufactured after the War made use of floral patterns on a raspberry backdrop.

One distinct subset of Sarough rugs is called Feraghan or Farahan Saroughs. These are room-sized carpets with an extremely fine weave comprised of asymmetrical wool knots on a cotton background. Farahan Saroughs typically showcase traditional medallion patterns surrounded by a floral border in a soft apple green or pistachio color.

Distinguished Designers from Arak

Some Arak rug designers became very well known within Iran for the carpets produced from their designs. Among these designers were:

• Isa Bahadori: Born in 1908 in Arak, Isa Bahadori gained international prominence when one of the rugs he designed won a coveted gold medal at the Brussels Exhibition.

• Asadollah Daqiqi 1905 – 1962: Asadollah Daqiqi learned the art of carpet design at the Mirza Abdollah Raisabadi School in Arak, and went on to establish one of Arak’s leading rug design centers.

• Zabihollah Abtahi: In the early part of the 20th century, Arak’s most famous rug designer was Zabihollah Abtahi who got his start in the rug industry in 1907 at the age of ten. Zabihollah Abtahi is best known for his exquisite Arabesque and Palmette Flower designs.

- Asadollah Abtahi

- Abdolkarim Rafiei

- Asadollah Ghaffari

- Jafar Chagani

- Seyed Hajagha Eshghi (Golbaz)

- Hosein and Hasan Tehrani

- Zabihollah Abtahi

Are Sarough Rugs Still Being Made in the Traditional Way in the Region?

Carpet weavers in Arak continue to hand produce beautiful Sarough rugs today. Sarough rugs continue to be created by artisans who adhere closely to traditional hand-looming methods. Modern consumers have more sophisticated tastes when it comes to subtle colors, so Sarough rugs are no longer re-dyed after they are woven to intensify their hues.

Sarough carpets are woven from high quality wools using the traditional Persian knot, which means they will stand up to decades of use. Elegant, beautiful and durable, Sarough carpets are among the most popular carpets coming out of Iran today.